Glen’s SF East Bay Real Estate Market Update

August 31, 2020

Here’s a summary of what’s going on in the San Francisco East Bay real estate market as of August 31st. I’d like to start out with a quick quote coming from Zillow and Rismedia:

“More sellers are making their way onto the market, but it’s still not enough to offset a supply shortage as a frenzy of buyers look to take advantage of low interest rates. According to Zillow’s most recent Weekly Market Report, buyer demand is still outpacing new supply.”

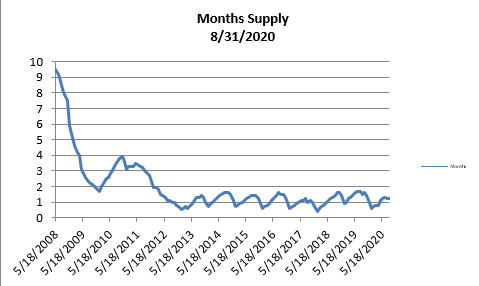

Yes, sales are up. Pendings are up by 24% compared to last year. Inventory on the other hand is down. In fact, it’s the lowest I’ve seen for an August since I started tracking statistics going back to 2008. We have a 36 day supply of homes for sale today. Last year at this time, there was a 45 day supply.

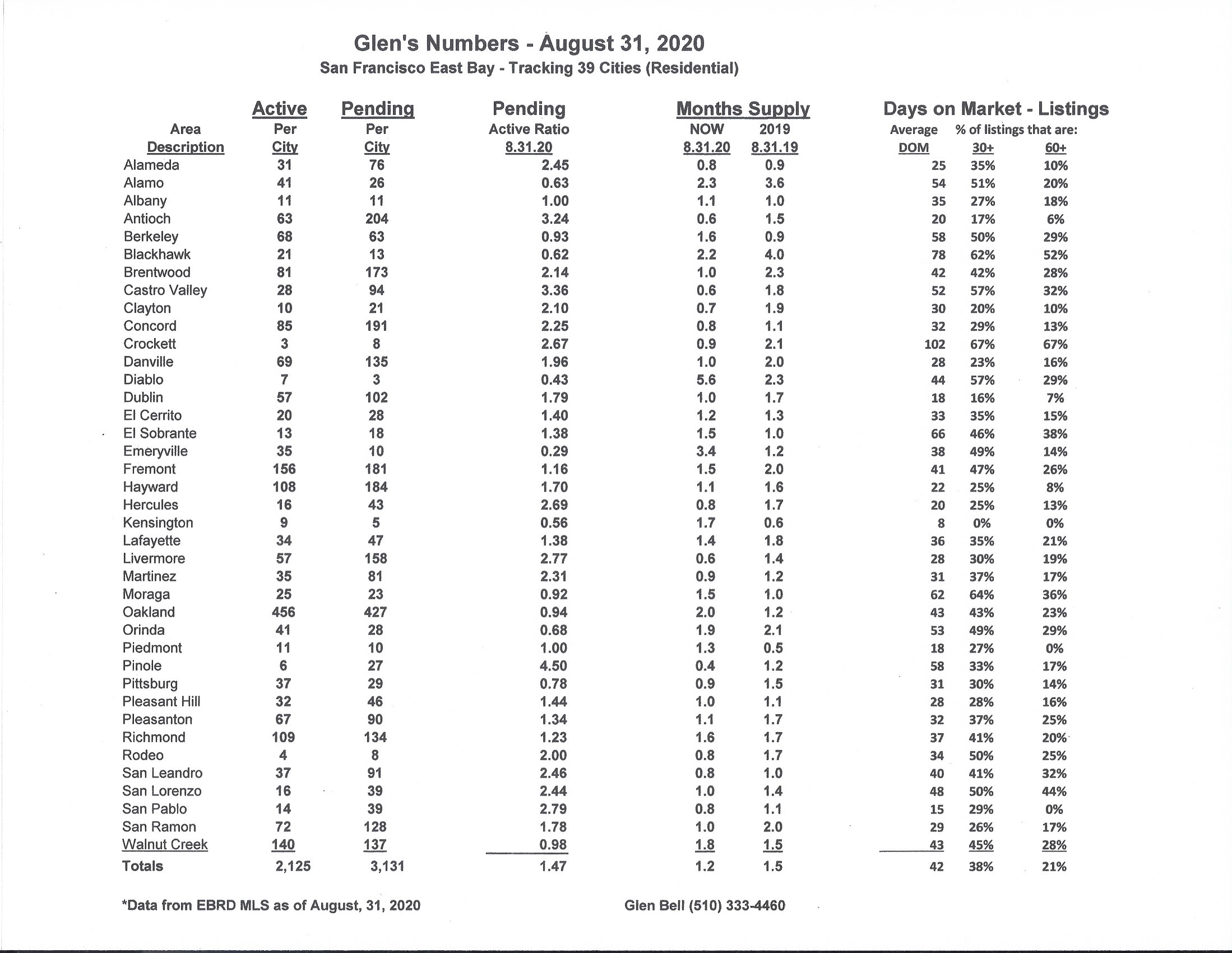

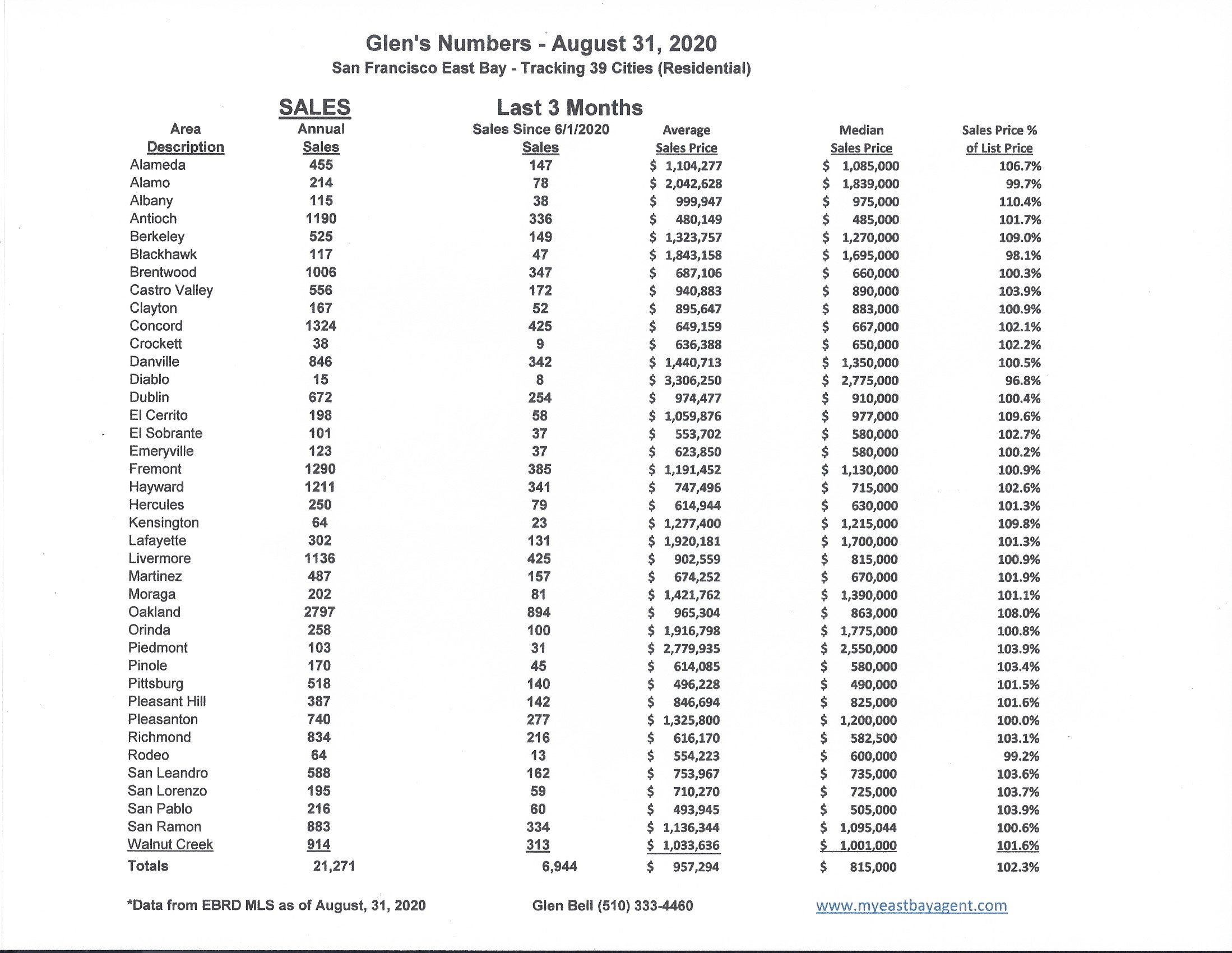

Here are some highlights for the 39 East Bay Cities that I track:

Sales are up from last month, but similar to what we saw last year at this time. Although there was a big “pause” in the market mid March through mid May due to COVID-19 Shelter in Place, we’ve bounced back, picking up where we left off early spring in what now looks to be a strong sellers market again. Prices continue to move upward, showing an 8.7% increase from last August’s median price point. However, it’s a bit of a mixed bag. More homes seem to be “sitting,” and taking longer to sell. We’re seeing more price reductions with more transactions falling out. Buyer’s are attracted to affordable, move-in homes with curb appeal as long as these rates remain at record lows.

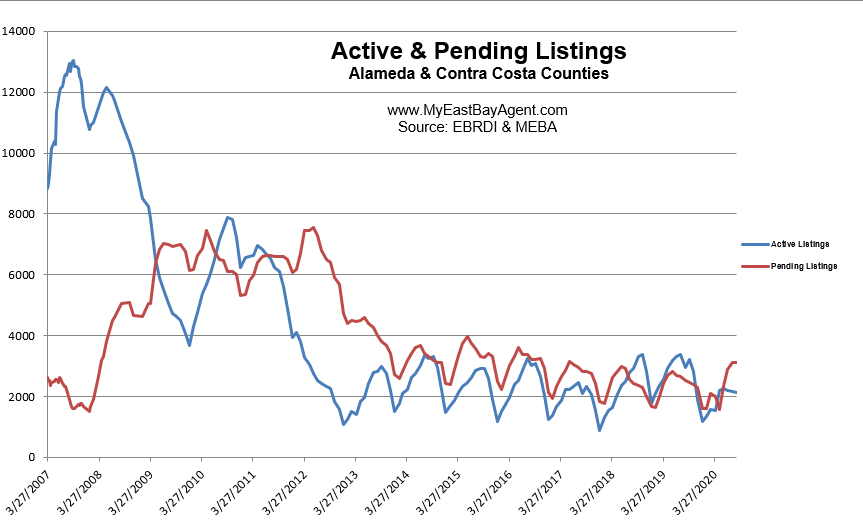

Inventory remains relatively flat in August. This again, as in June and July, was unexpected. We normally expect to see more inventory by now. Our inventory available is 28.2% lower than what we saw last year at this time. This represents a 36 day supply of homes, compared to a 45 day supply last year at the end of August. This is the lowest I’ve seen for an August since I started tracking numbers in 2008. I’ve made this statement now four months in a row. The number of pendings improved only slightly compared to July, a good sign that we still have buyers. The number of pendings are 24.4% higher when compared to last year at this time.

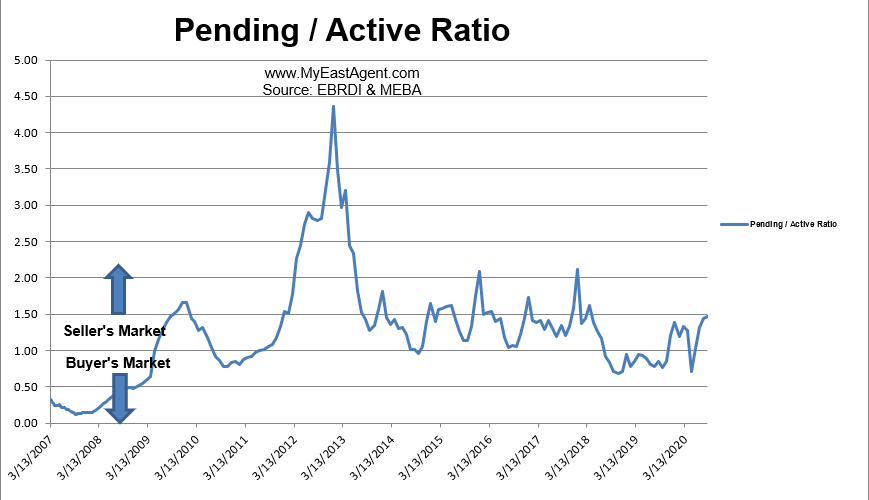

The pending/active ratio continued to move upwards, moving even more into a sellers market similar to what we saw at the beginning of the year. This is much higher when compared to last years’ number of .85. We’re now at 1.47. It’s the strongest market favoring sellers since the beginning of 2018. The pending/active ratio has been a benchmark that we’ve used as a measure of supply and demand to determine whether we’re in a buyer’s or a seller’s market. Typically, a number well above 1, (less inventory with more pendings) favors sellers. A number below 1 favors buyers.

- The month’s supply for the combined 39 city area is 36 days. Historically, a 2 to 3 months’ supply is considered normal in the San Francisco East Bay Area. As you can see from the graph above, this is normally a repetitive pattern over the past four years. Supply is less when compared to last year at this time, of 45 days.

- Our inventory for the East Bay (the 39 cities tracked) is now at 2,125 homes actively for sale. This is fewer than what we saw last year at this time, of 2,958. We’re used to seeing between 3,000 and 6,000 homes in a “normal” market in the San Francisco East Bay Area. Pending sales increased to 3,131, higher than what we saw last year at this time of 2,516.

- Our Pending/Active Ratio is 1.47. Last year at this time it was .85.

- Sales over the last 3 months, on average, are 2.3% over the asking price for this area, lower than what we saw last year at this time, of 3.0%.

Recent News

The Future of California Real Estate: Can the Golden State Survive?

By Clare Trapasso, Realtor.com, September 3, 2020

California has long captured the nation’s imagination with its promises of the rich life, from the days of the gold rush to the rise of Hollywood and its star-making machine, to today’s booming tech sector. With its breathtaking shoreline and strong economy, the state has become indelibly known as a place abounding in opportunities—for those eager to seize them.

Lately, however, California’s luster seems to be dimming.

A severe housing shortage, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, had led to the most expensive home prices in the nation. Wildfires this summer have devastated the northern part of the state. In the midst of a deep recession, many Californians are being priced out of their communities. Others are questioning why they’re shelling out so much money each month to live there—especially with companies in places like Silicon Valley allowing employees to work from home, wherever in the world that home may be.

It’s all converging at once to test the state’s true appeal. Despite the odds, can the Golden State’s real estate market remain, well, golden?

“Nobody in their right mind would bet against California,” says real estate professor Christopher Leinberger of George Washington University, in Washington, DC. However, “the Golden State can’t be golden forever with the ridiculousness of the home prices.”

California’s home list prices reached a record high in August—and have experienced the second-loftiest increases in the nation, according to the latest data from realtor.com®. (Only Utah saw bigger price gains.) Nine of the 10 most expensive metropolitan areas in the nation are in the state. (We included only the 300 largest metros, which encompass the main city and surrounding suburbs, towns, and smaller urban areas.) The state’s median price tag was $720,050 in August—up a jaw-dropping 23.7% from a year earlier.

That’s more than 10 times California’s median household income of $70,489 in 2018, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau data.

The price hikes are due to the dearth of homes for sale. The shortage has been going on for years, but it’s been compounded by the COVID-19 crisis. Shut in their abodes for months on end, Americans are seeking larger homes for working and schooling their children. But there simply aren’t enough properties to satisfy demand, with the number of new listings down nearly 11.1% from August of last year on realtor.com.

Leslie Appleton Young, chief economist of the California Association of Realtors®, attributes some of that rapid run-up in prices to rich, white-collar workers who can now telecommute buying up luxury properties in more remote locations. In July, sales of homes priced at $3 million and up increased by about 76.6% year over year, she says. Homes priced at $1 million and up now make up about 20% of the state’s sales.

“The challenge is, you have the next generation of home buyers, [but] it’s very difficult to buy in California,” she says. “We’re losing people who simply can’t afford to be here.”

Many Californians were already being priced out

The lack of affordable housing is partly responsible for the nearly 3.25 million Californians who left the state from 2014 through 2018, according to the latest U.S. Census data. It’s also led giant tech companies like Google and Facebook, whose well-paid employees are partly responsible for the acceleration of prices in the San Francisco Bay Area, to pledge to build affordable housing in the area.

Looking at migration patterns in the U.S., “people have been leaving California and the Bay Area in higher numbers than they have been arriving,” says Patrick Carlisle, chief market analyst in the Bay Area for real estate brokerage Compass. “That outflow was being balanced by foreign immigration for years.”

More recently, however, that inflow of foreigners has declined.

Before the pandemic, Gov. Gavin Newsom boasted California had the fifth-largest economy—in the world. But COVID-19 has dealt the state’s economy a blow. California had a 13.3% unemployment rate in July, the sixth-worst in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“The housing supply in California is the No. 1 priority,” says Dowell Myers, a housing demographer at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles. If the situation doesn’t improve, the lack of housing “will stifle employment growth and undercut the economy,” he says.

The quality of life could deteriorate enough to spur more folks to leave and deter others from moving in, he says.

Wealthier tech workers can still afford to drop nearly $1.2 million on a median-priced home in Silicon Valley’s San Jose metropolitan area, according to realtor.com’s August list prices.

But many others realize they can pay a fraction of that to live in other hip cities with growing tech hubs, like Austin, TX, with a median list price of roughly $400,000; Salt Lake City, at $490,000; and Nashville, TN, at $396,000. Even other West Coast tech hubs like Seattle and Denver are significantly cheaper, with median prices of $625,000 and almost $540,000, respectively.

Departing residents are “much more of a threat than a fire or an earthquake” to the state, says Myers. Although it attracts well-educated, high-earning millennials from other states as well as foreigners, California might see these higher-earning transplants leaving after a few years.

“They feel like they can’t possibly live where they want to live and buy a house,” says Myers. “California could hold more of the recruits if it had cheaper housing.”

George Washington University’s Leinberger blames NIMBY (“not in my backyard”) attitudes, which have stymied the creation of new housing throughout the state. While many residents support new construction, they don’t want it in their own communities. They worry that creating more dense housing, such as apartment, condo, and townhome complexes as well as smaller homes, could lower their own property values. They also say it would tax the existing infrastructure, like schools and local services, and exacerbate traffic issues.

Even well-meaning local regulations can drive up building costs and lead to long delays that can stretch over a decade between an application being submitted and a shovel going into the dirt.

“This is a self-inflicted wound,” says Leinberger of the housing shortage.

Could the pandemic prompt more people to leave California?

Although there has been a steady stream of Californians leaving their home state for years, the pandemic could accelerate that trend.

With more white-collar workers able to work remotely, some are heeding the siren song of more affordable homes, lower taxes, and a cheaper cost of living outside California’s borders. Others are remaining in state, but forsaking the expensive cities and moving into less-expensive areas.

“In the short term, California is going to see more people leaving due to the high cost of living combined with the ability to work remotely,” predicts realtor.com Senior Economist George Ratiu.

“People are willing to pay a premium to live there,” says Ratiu. “Perhaps that premium is being reevaluated by a lot of younger people.”

California could see winning and losing real estate markets

While some of California’s housing markets may be forced to slow down, others will likely keep accelerating.

“California’s a big place. You’re going to have winners and losers within the state,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics. “The housing markets in those urban cores are struggling. That will continue throughout the pandemic.”

In the Bay Area, sales for single-family homes in San Francisco and larger residences in the more suburban counties have been brisk while condo sales within the city limits have dropped off as a result of the pandemic, says Bay Area analyst Carlisle. That’s driven by wealthy, white-collar workers who are able to work remotely.

In addition to the surge in interest in expensive, sprawling homes north of San Francisco, in Marin County and Napa and Sonoma, buyers with means are trading their rentals and smaller homes in high-priced, urban areas for larger homes in more affordable, inland communities in California. Some are leaving the state altogether for hip cities with strong job markets.

However, many more are staying put. Southern California, including Los Angeles and San Diego, could fare better than Northern California’s Bay Area as it’s a little less expensive, says Matthew Gardner, chief economist of Windermere Real Estate. Residents who work in the entertainment and other Southern California industries may be less able to work from home as the Bay Area tech workers.

“We’re not talking about cities being abandoned,” says Carlisle. “Shifts in markets are shifts in degrees. Except for something like the housing bust of 2008, [markets] slow down.”

And no matter what trials it’s currently going through, California is still, well, California.

“It’s hard to envision a large exodus,” says Appleton Young. “We are [still] the tech hub, we’re the entertainment hub, we’re rich in natural resources and natural beauty.”

Zillow: Buyer Demand Continues Outpacing New Supply

By RISMedia Staff, August 31, 2020

More sellers are making their way onto the market, but it’s still not enough to offset a supply shortage as a frenzy of buyers look to take advantage of low interest rates. According to Zillow’s most recent Weekly Market Report, buyer demand is still outpacing new supply.

For the week ending Aug. 22, newly pending sales were up 16.5 percent YoY—the biggest increase since mid-February. In addition, homes are selling faster—coming off the market in just 13 days, which is also 13 days sooner than last year.

While the inventory gap is narrowing, new for-sale listings were still down 10.6 percent YoY that week. And because of the quick market turnaround, total for-sale inventory has fallen further below last year’s level—as of last week, there were 29.8 percent fewer homes on the market than the same time last year.

This is causing prices to continue rising. For the week, the median U.S. list price was $345,255—8.3 percent higher YoY and the biggest annual change since the week ending July 13. The median sale price was $277,500—5.1 percent over last year’s number.

Home Prices Hit Record Highs. Is It a Bubble About to Burst?

By Clare Trapasso, Realtor.com, Aug 24, 2020

The nation’s surging home prices don’t seem to care about the recession the country is mired in. They can’t be bothered by the deadly coronavirus pandemic or the double-digit unemployment that’s come as a result. Instead, prices are defying logic, expectations, and even belief, as they shoot up to record highs amid an unprecedented health and economic crisis.

It has all led some to wonder: Are some markets getting too hot? Could a significant correction be around the corner?

Such questions have become louder in recent weeks, in the face of some startling growth numbers, particularly in some high-priced California and less expensive Rust Belt, Midwestern, and Southern markets.

In some of these metropolitan areas, prices have shot up by more than 20% in the past year alone. Just how sustainable is this seemingly irrational home price exuberance, anyway? Could we be entering the dreaded bubble territory once again?

Nationally, the median home list price rose 10.1% year over year in the week ending Aug. 15, according to the most recent realtor.com® figures. No one predicted such a dramatic increase compared with 2019—when the economy was strong, no one had heard of COVID-19 and social unrest hadn’t exploded.

In fact, many experts predicted prices would flatten, if not fall.

Reality check: If there is a current-day bubble, it bears little resemblance to the gigantic bubble created by subprime mortgages, which burst into the Great Recession. Then came the mass foreclosures, plummeting home values, and the scores of homeowners suddenly underwater on their mortgages.

This year’s sky-high prices are driven by a rush of buyers competing for a very limited supply of properties. More demand than supply equals higher prices.

“Some markets are overvalued,” says Javier Vivas, realtor.com’s director of economic research. “Growth of prices in a recession is pointing in that direction. Some markets are seeing increased risks of price corrections.”

Instead of another real estate fire sale, certain parts of the country could see price hikes slow down or flatten, or prices even come down—by just a little. That could happen if prices rise so high that homeownership becomes too expensive for the majority of would-be buyers.

So instead of a bubble popping, it’s more that home prices could come back to reality.

Typically, market corrections happen fairly quickly, within two or three months, as priced-out buyers make a beeline for the sidelines, says Vivas. This year, record-low mortgage interest rates are muddying the picture.

Rates under 3% for the first time ever are driving more buyers into the market and allowing them to stretch higher on what they’re willing to pay. Lower rates mean lower monthly mortgage payments. That’s allowing sellers to ask—and receive—more for their properties.

Those who weren’t able to buy in the spring because of the pandemic—along with buyers desperate for larger, single-family homes with big backyards after sheltering in place for months—are adding to the rising demand.

However, worries about the pandemic have led to a record-low number of homes for sale, as sellers decided to wait out the health crisis. Meanwhile, many builders were forced to pause projects in some parts of the country. That’s led the scrum of competing buyers to bid up prices in an effort to secure a property.

Most striking in 2020’s home price ramp-up is the fact that’s happening in some of the nation’s most expensive and cheapest markets alike.

“In the inexpensive markets, you have a ton of space for prices to grow. You can see them overheat and absorb that overheating better,” says Vivas. That’s unlike the already high-priced coastal areas.

“The outlook for them is a faster and broader correction, [with] slight declines in home prices.”

Price corrections could happen by the end of the year in areas where prices have risen very high—along with local unemployment rates, says CoreLogic’s chief economist, Frank Nothaft.

Why won’t we see another Great Recession-era housing bubble?

The sky-high prices of 2020 are being driven by an influx of buyers bidding up prices on a historically low number of homes on the market. Until more properties come online, that dynamic is unlikely to change.

The Great Recession had the opposite problem: There were many more homes available than qualified buyers.

In the aftermath of the housing bust, it’s become harder for buyers without good jobs and strong credit to score mortgages. This weeds out riskier borrowers. And unlike the last go-around, when builders were erecting residences at what seemed like a break-neck pace, the under-building of the last few years has exacerbated the housing shortage.

Even if the economy doesn’t improve by next year and a vast swath of Americans remain unemployed, we are not likely to see the flood of foreclosures that characterized the housing crash, partly because government protections could be extended.

“It doesn’t feel at all like last time, when the market was getting all pumped up by easy mortgage credit,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics.

Some of the nation’s most expensive housing markets are getting costlier by the day.

Median list prices surged in the Santa Maria, CA, metropolitan area, which includes tony Santa Barbara, CA. They were up no less than 44%annually in July, to reach $1,795,050.

That was the largest increase in the nation, despite the relatively high percentage of locals out of work (12%). In the Los Angeles metro area, prices increased by 24%, to a median $994,150.

They were considered two of the country’s potentially most overvalued markets, due to their massive price hikes, despite double-digit unemployment rates.

Gerd-Ulf Krueger, president of Krueger Economics, doesn’t expect prices in the Los Angeles area to slow down, let alone fall, unless residents on the higher end of the income spectrum (i.e., the 1%) lose their jobs or receive salary cuts.

While the unemployment rate in the Los Angeles metro area topped 18%in June, those at the top have been largely spared the financial pain experienced by those on the lower income rungs.

“The income gaps are very severe” in the Los Angeles area, Krueger says. The problem has also been exacerbated by a lack of new construction in the region, making it even more difficult for buyers to find affordably priced properties.

Sellers “are a little over-enthusiastic. They are realizing the wealthier or more affluent middle class still have money to buy homes.”

Pennsylvania has the most metropolitan areas that have experienced both the highest price increases and high unemployment. This puts them at risk of price corrections.

In the Pittsburgh metro, median list prices rose 25% in July compared with a year earlier, a rise that could make the market overvalued. (Metros include the main city, surrounding suburbs and towns and smaller urban areas.)

“It’s just a product of supply and demand,” says Pittsburgh-based real estate agent Bobby West of Coldwell Banker Realty Services. “There are so few homes that are coming on the market, those that do are selling within 24 hours, with more than one offer.”

“It was a mad rush” when real estate services reopened after the pandemic shutdown, says West. “My bet is things will cool down into the fall and the winter months as far as pricing goes.”

However, with a median list price of just $249,950—about 40% less than the national median—prices still have room to rise.

The old steel town of Allentown, PA, and the surrounding metro area, have seen price increases comparable to Pittsburgh’s, as the supply of homes for sale has dwindled. Median list prices shot up 21% year over year, to reach $278,500 in July, according to realtor.com data.

The area is benefiting from folks leaving the New York City and Philadelphia areas and heading to Allentown, where they can afford more spacious homes—particularly if they’re now able to work remotely due to the pandemic, says local Keller Williams real estate agent Faith Brenneisen. The city is about 90 miles west of New York City and 60 miles north of Philadelphia—and its homes are selling for a fraction of the prices in those two cities.

She’s receiving seven to 10 offers per listing and offers running $20,000 to $30,000 over asking for homes priced in the sweet spot of $150,000 to $250,000.

Median list prices were up in Reading, PA, by 24% to $272,450 in July, compared with the previous year. In Wichita, KS, they rose 22% to $246,150, they were up 19% in Fayetteville, NC, to $219,800; they increased 18% in Philadelphia to $340,000; they grew 17% in Canton, OH,to $190,000 and 16% in Mobile, AL, to $215,350. All of these areas also had unemployment rates at or above 10% in June, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link